THE MEMORY OF MY GODFATHER, THE “LIFE ARTIST” / Mária Weltz Fülöpné

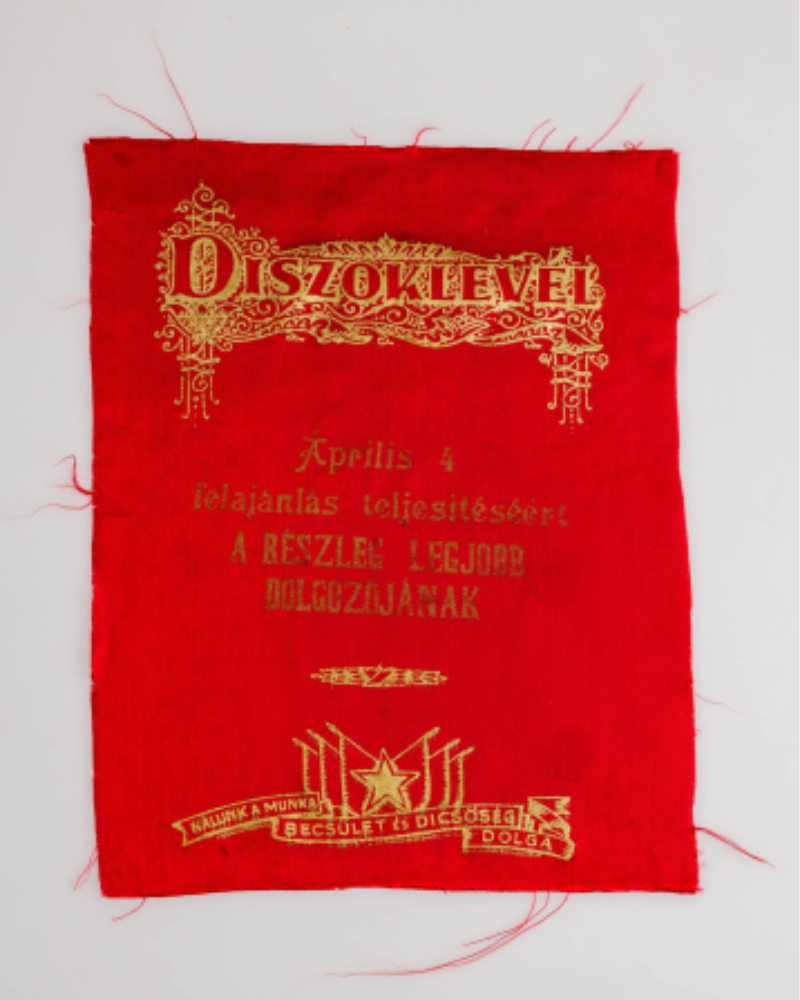

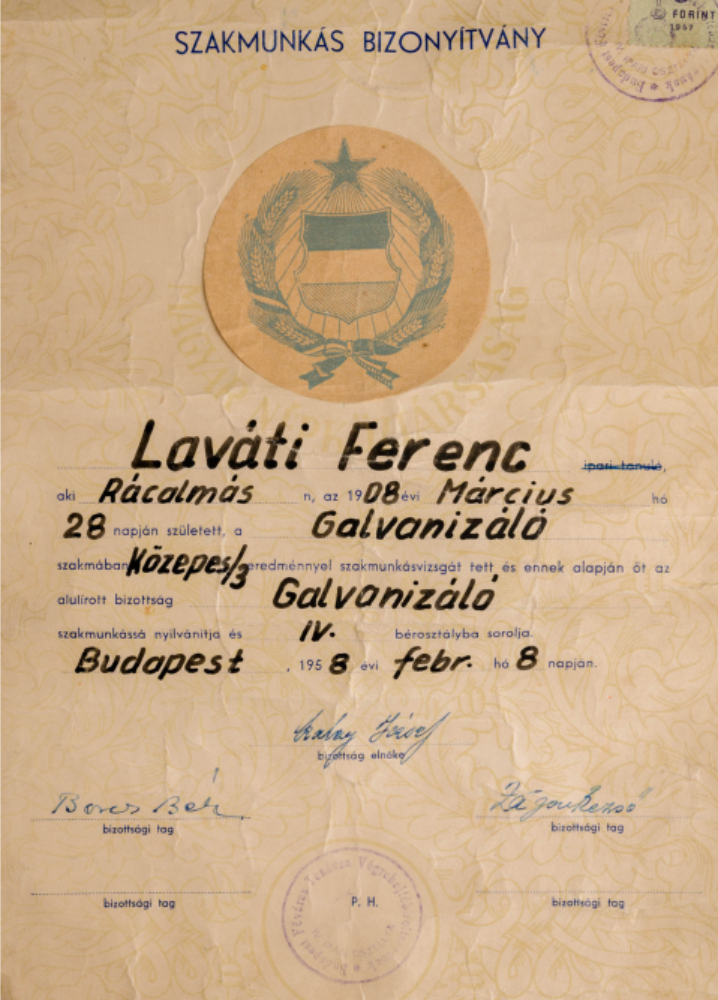

Besides the adventurous stories my godfather told me, I also preserve the objects that belonged to him: his photo, his business card, as a wine wholesaler, his skilled worker certificate, a certificate of distinction in red cloth, and a medical report.

My godfather was the eldest child of a large family. This family was like the one in the saying: “your child and my child are beating up our child.”

Grandpa Lováti was a fisherman. He constructed a wooden hut atop a raft: he asked ships to tow him upstream to Budapest, then he drifted downriver to Kalocsa, fishing in the Danube. He stopped wherever there was a market and sold the fish. My godfather helped the women take home their purchase, then he asked permission to search the attic for used clothes. He said he was hoping to find clothes for his large family. Then he cut the fancy buttons off the clothes, and sold them to a haberdasher in Budapest. This is how he bought his first suit, which he wore when he applied for an assistant waiter’s position at a pub in Buda.

He was a handsome lad. He caught the eye of the innkeeper’s wife, who was twelve years older than him. In the end he seduced the woman and married her. They used her money to open their first pub. My godfather brought his family members, including my mother, to Budapest to work at the business. He provided my mother’s dowry, and married her to a butcher, my father. The business prospered because he was a good businessman, and he opened three more pubs, all managed by his siblings, because, as he said, at least they would not steal from him.

He used the Anti-Jewish laws to his advantage, and became a frontman. As a wine wholesaler, he had a film made which was then shown in the cinemas: This is How Lováti Harvests in Csengőd. Everyone knew his name in Angyalföld.

He was not conscripted for a long time, due to his money and his connections. At last, he was taken straight to the front in late 1942. He attached a carriage to the train full of wine and rum. This carriage was uncoupled on the way, but he got to the front just in time for the Soviet breakthrough at the Don River, and he was captured. He was a prisoner of war for five and a half years, but even then he managed to turn the situation to his advantage. He prevented a fire in the camp, for which he was given small benefits, and he was among the first to come home. Before that, he was taken to Moscow to see Lenin. He told us a lot about his captivity and about the Russians. Once they were driven through a Russian village, and there was a boy who ogled his warm felt boots, so he had to give them to him. When they got to the end of the village, the boy was waiting for him. He brought a warm loaf of bread, which meant life itself. They were only given rotten fish in the camp, but my godfather would not eat that. Instead, he cut the barks of the trees, and licked the sap. It was his common sense that helped him, not the three grades he completed at school. He wrote his letters pecking on a typewriter, because he could not even write properly. When a wound on one of his fingers became infected, he opened it with a razor blade, so he did not die of sepsis.

He came home in 1948, weighing 41 kilos. He arrived in Debrecen, where he was examined and diagnosed with lung disease. (orvosi lelet) He was given a train ticket to Budapest and 20 forints. He first went to a pub and ordered a glass of wine to see how much the forint was worth. At home he found that his house and two of his pubs had been confiscated, and the third pub was half demolished by a bomb. He then learned electroplating. He was awarded a “Distinguished Worker” medal at his workplace.

The half-bombed restaurant in Béke Square, which was in the name of my godmother, was accidentally left in their possession. There was a flat in the part that remained intact, and I moved there. When it was demolished, I was given a council flat. Thus my godfather was able to give even when he had nothing left.

He was the eternal survivor. He never gave up, and taught me to do the same.