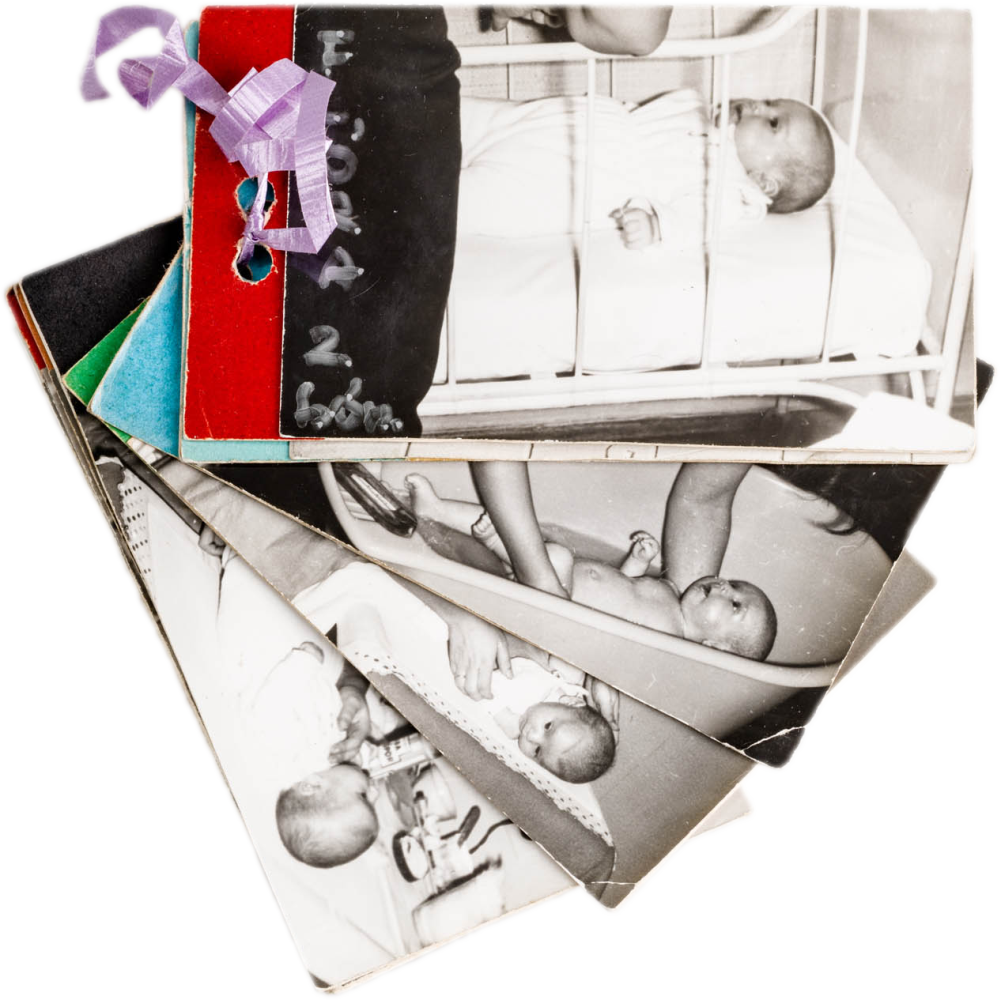

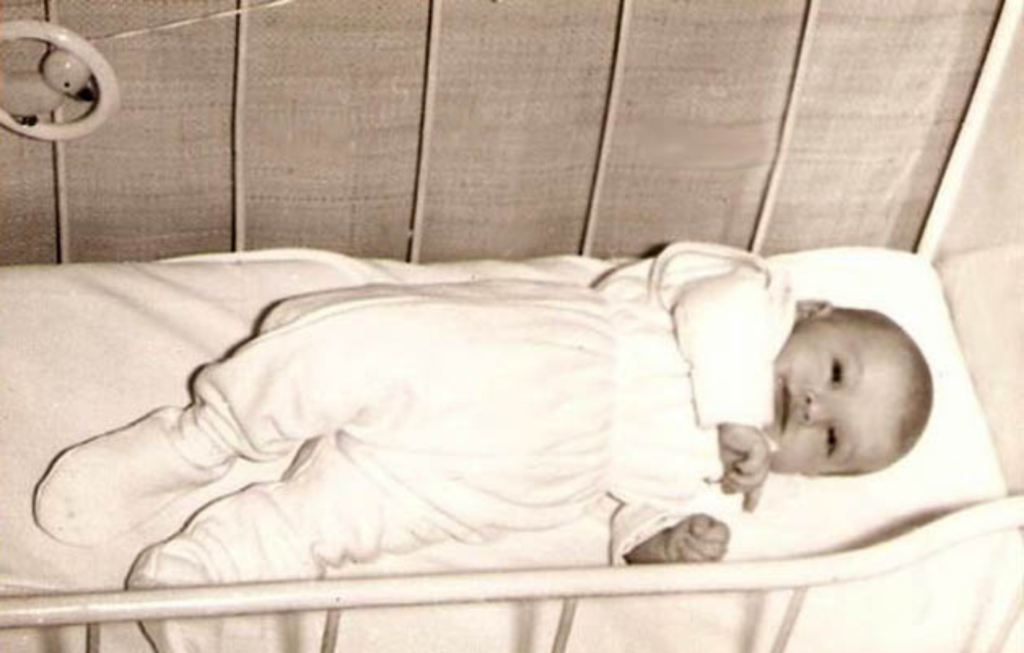

THE STORY OF A CRIB / Nóra Előd

The crib in the story served our family and friends for generations: it was the first home of more than 20 (!) babies. It came into the possession of my family in 1913, the year before World War I broke out. The babies who spent the first months of their lives in the crib were:

– Margitka (1913), who married an army officer coming from an old Hungarian family of petty nobility, which saved her from the ordeals of the persecution of the Jews, but could not save her from the hardships of being a Hungarian after the Treaty of Trianon, or from worrying about a husband who took an active part in the antifascist resistance, deserted from the army, and had to go into hiding; she did her best to save, hide and help whomever she could and whoever needed it; she spent her eventful life in serving the community with dedication and honour, and died as a grandmother to eight grandchildren;

– Cili (Margitka’s sister, 1914), who could “only” learn a trade due to the numerus clausus, but she excelled at it; she came back from the concentration camp weighing little more than thirty kilograms, but she grasped the new opportunities and passed her school-leaving exams during an accelerated procedure, even though she was no longer young, then obtained degrees in two different professions, and worked as a teacher to the end of her life, with great enthusiasm and surrounded by love;

– István (the third sibling, 1917), about whom we know only that he was conscripted for labour service in 1942, where he “disappeared”;

– Gyuri (cousin, 1918), who went to university in spite of the numerus clausus, then just after graduation was carried off to do labour service on the Russian front in 1942, where he died of “exhaustion”;

– Laci (Gyuri’s brother, 1921), who left his diary to posterity in four thick chequered notebooks, which bear testimony to his struggles with himself, with the profession forced upon him by the numerus clausus, with adolescent love, with the situations and roles in which history placed him; the last entry documents the day he left to die in labour service on 4 June 1944 (the diary was published with the title The Chequered Notebooks in 2015);

– Andris (Gyuri and Laci’s brother, 1925), who was called up for labour service right from the classroom, at the age of nineteen; no news ever came about him after that;

– Veronka (second cousin, 1928), who at the age of 16 was saved from a death march at Hegyeshalom by Wallenberg and by her own pluckiness; the historical events – the internment of her social democrat father and other occurrences which had a similarly disastrous effect on the family – soon turned her from her communist convictions, so that in 1956 she was on the side of the revolutionaries; she waited patiently for her husband, who was first sentenced to death, but had his sentence commuted to 15 years in prison; in fact, they got married in the prison, with two prison guards acting as their witnesses; when she had to go to prison herself to serve her term which was luckily shortened to one year due to an amnesty, she left her one-year-old son with her stepmother; when, after all this, she remained alone, she dedicated her life to raising her child and to her medical profession until she died at an advanced age;

– Panni (Veronka’s sister, 1931), who, like her siblings, learned in 1944 that she was not Roman Catholic, but in fact Jewish; her life was saved by Gábor Sztehlo’s child-rescuing mission, but she lost her mother and her home; unlike her hardier sister, she could never come to terms with her loss; when her father was interned just after returning from Russian captivity, she tried to make herself believe that this was an individual “mistake” committed in the name of a “greater good”, but she could not keep it up for long; after 1956, she was forced to leave the country due to the threat to her husband’s life, who was a revolutionary commander; she left behind her three-year-old child (whom the state held “hostage” for 4 years!), who was raised by the same relatives as her sister’s son; approaching 90, today she is the oldest member of the family, and continues to live abroad;

– Kati (1932), whose entire life – except for her short but carefree childhood – was defined by fear: when she had to sew on the yellow star, she was afraid to show herself to her classmates (she never went to school again!); she was terrified when the world literally collapsed around her in the cellar of the yellow-star house; she was scared when she realised the dangers of the profession she had chosen (she became an army interpreter); she worried for two days when she could not find the key to the bookcase because she was convinced that her flat had been tapped, and from this moment on she was always searching for the bug; when the shooting started at the Radio building, she fled home in panic; in November 1956 she did not stop until she reached Paris, where she hoped to find peace, but when she heard the sound of the first explosion (of the fireworks!) on 14 July, she crawled out of her dorm room onto the corridor on her belly; when she was first able to come home after nine years, she was frightened that she would not be allowed to go back; in the meantime, she became a scientist of European fame, one of the best in her profession; the only thing she was not afraid of was cancer: she firmly believed that she would be cured – but there she was wrong;

– Little Nóra (cousin, 1935), who survived the war, but lost her ten-year-old younger sibling in an accident in 1945 (!), while the rubble was cleared; she was rejected year after year by the College of Fine Arts she dreamed about because of her “class-alien” stepfather; therefore, she was among the first who left the country in 1956, and became a successful fine artist in Canada;

– Peti (Veronka’s and Panni’s brother, January 1936), who also tided over the hard times in a Sztehlo-home, but then deleted all of it from his memory; after he lost his mother and home, he started a new life looked after by his aunt; a few years later, he also lost his father, who had just returned from Russian captivity (Tököl internment camp, 1950–1953); he witnessed the ordeals his sisters and brothers-in-law went through in 1956; in spite of all this, he graduated from the Music Academy, and became a pioneer of Hungarian jazz, which had an underground status for a long time, and he became an outstanding figure in the history of Hungarian jazz as a virtuoso vibraphone player;

– Nóra (Kati’s sister, May 1936), guardian and chronicler of these life histories and events, whose autobiography was published with the title Hétszínvirág: Nyolc évtized magántörténelme [The Flower of Seven Colours: Eight Decades of Personal History];

– Little Laci (nephew, 1942), who was in great need of the well-worn crib because his parents, who “repatriated” after the re-annexation of Northern Transylvania, could only bring what was strictly necessary with them; when he was twenty, he attempted to disentangle the family connections confused by politics and history, but he gave up, abandoned his fairly promising career as a poet, and now is growing old alone and retired from the world;

– Tibi (1946), who was born nine months after the Russians took his mother to “peel potatoes”; after his turbulent childhood and rough adolescence, his family lost track of him; only the news came back that he settled and grew up to become a happy husband and father;

– Little Kati (cousin, 1946), who could have had good prospects due to the time of her birth, but instead she had to cope with a historical, political and family legacy which was hard to understand or accept; his father had lied about being a Jew, graduated from the Ludovica Academy, and became an officer in Horthy’s army; later he actively participated in the antifascist resistance movement, deserted the army, went into hiding, then crossed the frontline in secret, and arrived back in Hungary together with the Debrecen government; he was allowed to keep his officer’s rank as long as he directed the demining of the Danube, but was interned afterwards as a former officer of Horthy’s (Kistarcsa, 1949–1953); finally, after his release, he became a renowned military historian and found his peace; from the history of her maternal grandparents in the labour movement (social democracy!), Little Kati mostly comprehended the disfavour and the exclusion from both sides, and this necessarily led her to become an activist in the ranks of the democratic opposition;

– Marcsi (Panni’s daughter, 1953), who remembers the raid that occurred one night when she was three (January 1957); she was shaken awake and asked: “Where is your Daddy?” (children tell the truth!); “In Palis”, she answered, and went barefoot and in her pyjamas to find the telegram confirming her words (children are observant!); she was treated as a hostage by the state for four years to lure back her father, who had been sentenced to death in his absence; at the intervention of Mme Khrushcheva, who visited Paris in 1961, she was finally allowed to go to Paris to her parents, where she quickly forgot to speak Hungarian because she had had enough of being “different”; nevertheless, when her younger sister, already born in France, spoke in French, she snapped at her: “What is this gibberish? Speak normally, in Hungarian!”; now she lives in Paris, and she will not speak about her childhood memories to her own children and grandchildren at all;

– Gyurika (Veronka’s son, 1957), who helped her mother with his very birth, because due to this she was allowed to remain free until her trial, then her sentence was deferred so she could care for her child, and she only had to spend one year in prison; thus Gyurika was looked after by his grandmother in the second year of his life; he cried inconsolably when her mother set out early on a dark morning (1960) to visit her husband, who was serving his 15-year prison sentence in Márianosztra; when his grandmother tried to soothe him, he sobbed: “mother already left once, and she did not come back!”; he received these early childhood experiences as a “bonus” from his father, who had been to Auschwitz, and from his mother, who had been saved from the death march; the heavy legacy made him ill, and now he lives a difficult and joyless life, trying to preserve the memory of his parents for a forgetful posterity;

– Ádám (Gyurika’s brother, 1961), who was born exactly nine months after his father’s amnesty on 4 April 1961; he could not (would not?) face this heavy legacy: he went abroad as a teen, and continues to live there, doing neither too well, nor too badly;

– Flóra (November 1963), who learned early what was meant by the term “double education”: “if you repeat in school what you hear at home from your father (historian and political scientist Miklós Szabó, founder of the “flying university”), your Dad will go to prison”; in spite of this, she was an enthusiastic member of the pioneer movement, because Laci bácsi, the teacher who wore the red scarf, managed to create a cheerful world of trips, camps and football matches for the children, entirely free of politics; she received a defining intellectual, cultural and methodological legacy in the amateur theatre company; she found her place in the world as a versatile primary school teacher – as well as the mother of three and a grandmother – who has made good use of the tools of modern pedagogy;

– Lacika (1965), who did not know any of his grandparents, because the life of his family was disrupted not only by the Holocaust, but also by the communist seizure of power; his intellectual and ideological foundations were provided by a mother who became a devout Christian to escape the past of her family decimated in Auschwitz, and who was maimed in an accident caused by a Soviet military vehicle, and who raised her sons with steely determination;

– Zsófi (Flóra’s sister, 1967), who was less well suited for the kind of “initiation” that Flóra went through, therefore required more conspiring from her parents; after trying out various forms of communal activities, she found the pillar of her life in the folk dance movement, which defined her lifestyle and relationships; at the age of twenty (minutes before the unforeseeable Romanian revolution broke out) she almost married a young man from Kolozsvár (Cluj-Napoca) out of sheer solidarity, to help him escape Ceauşescu’s Romania; she was a real “lifelong learner”, who obtained qualification after qualification in complementary or even interchangeable fields, and could now be said to have found the perfect role as a teacher if the anomalies of public education had not interfered with her life and career again and again;

– Kinga (1976), the last known user of the family crib, who was born in Hungary, but was brought up on family legends telling about, on her mother’s side, the trauma caused by a forced resettlement euphemistically called “an exchange of populations”, expulsion from the “true home” remembered as the forever lost Garden of Eden, and slowly growing new roots in a different soil, and on the father’s side, escape from Transylvania, a train journey lasting several weeks, and the determination to start a new life.

There were two other babies who used the crib, but we no longer followed their history. The piece of furniture left the family and got to more and more distant acquaintances until we finally lost track of it. It probably found temporary refuge in an attic or cellar until it was at last discarded on one of the annual garbage collection days.