POSTCARDS FROM A CAPTIVE GERMAN SOLDIER / Marion Reichl

I was born in 1942, in the middle of bombing attacks on Munich. My mother and I were very sick and had to stay in hospital for a while to recover.

After we felt fit enough, we went to live in a small village on the outskirts of Munich, where my grandparents had a cottage for the weekends. My mother and I lived there completely alone with a little “dachshund”, my father had given to my mother before I was born.

We were nearly untouched by the war, but we could see U. S. airplanes flying towards Munich to unload their bombs on the city. When they came back, they dropped bombs into the nearby forest. As children, we were strictly forbidden to go near the woods. Once a U.S. airplane was shot down by our “flak“ and dropped into the trees not too far away from us. After a while my grandfather and my American grandmother joined us, because their flat and their shop in the city centre of Munich was burnt down during an Allied bombing.

I lived happily with my grandparents and my mother, together with our dog Bazi, some hens for eggs and goats for milk and once even a pig which was fattened for a friend. After it was slaughtered, we had to give a share to all the neighbours for not giving us away to the authorities, because keeping a pig privately was strictly forbidden.

My father was fighting in Russia, as many others. I did not know him, and I did not miss him.

In the meantime, he was fighting with the 6th army in the battle of Stalingrad. As a doctor of a whole company he survived in the “Theaterkeller“, was taken prisoner in 1943 and together with 100 000 comrades, they disappeared in Russian prison camps behind the Ural.

There was a little anecdote quoted very often by my father. Walter Ulbricht (later: the first General Secretary of the SED, GDR, the Socialist Unity Party of Germany in the German Democratic Republic), who was sought out to re-educate the German soldiers, once lined up the soldiers in the camp and said: “The wooden beams which will be the wagons to take you home are still little birch trees in the taiga.“ (“Die hölzernen Balken, aus denen die Waggons gemacht sind, die Euch nach Hause bringen werden, stehen noch als kleine Birken in der Taiga.“)

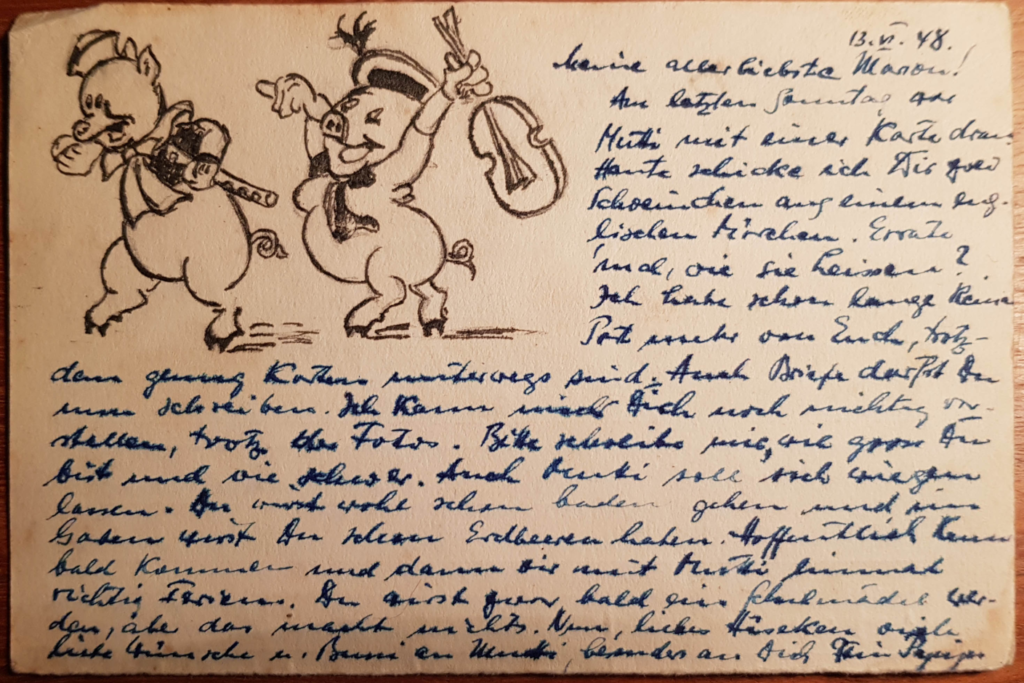

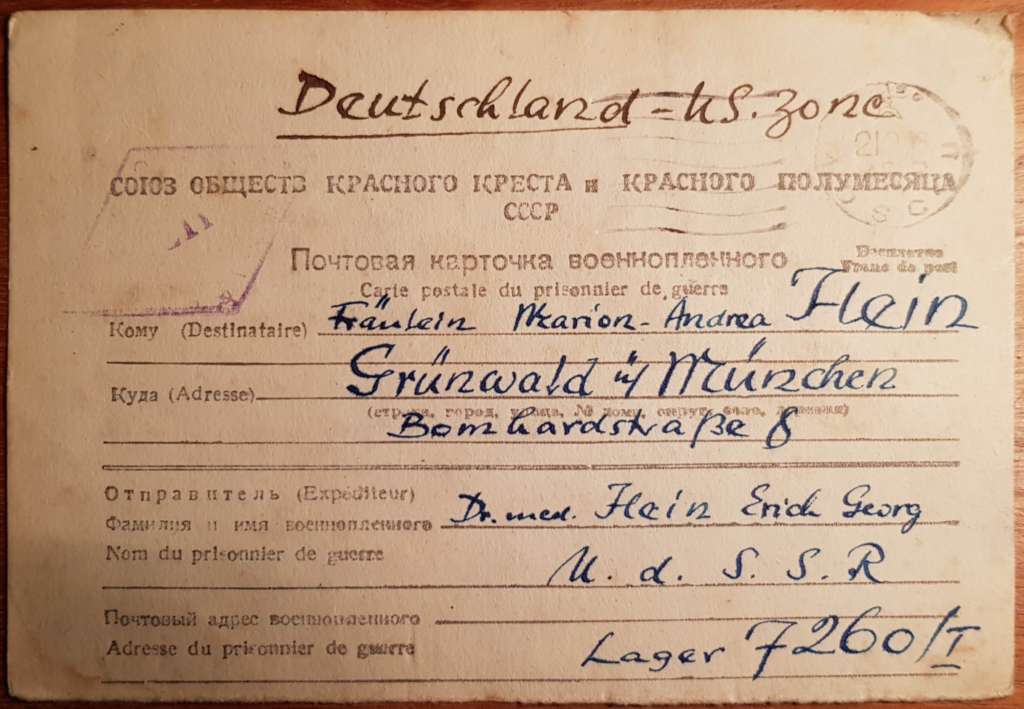

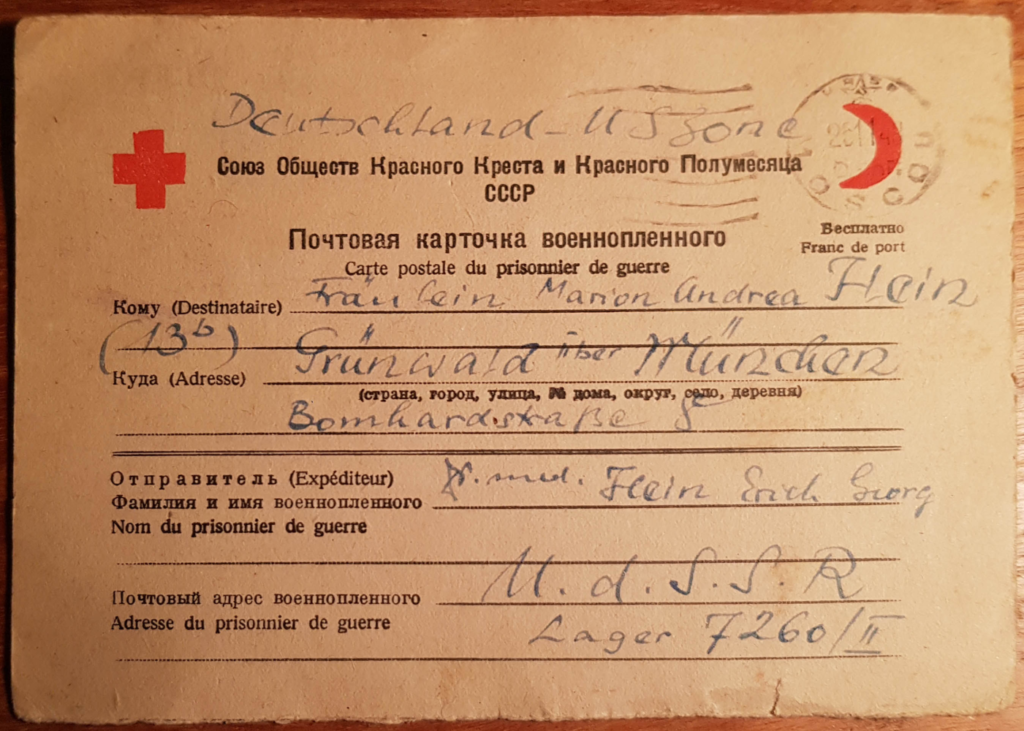

Sometimes the POWs were allowed to write a few words on cards and receive news from home. All letters were read and blackened in places where details about the camp were passed on.

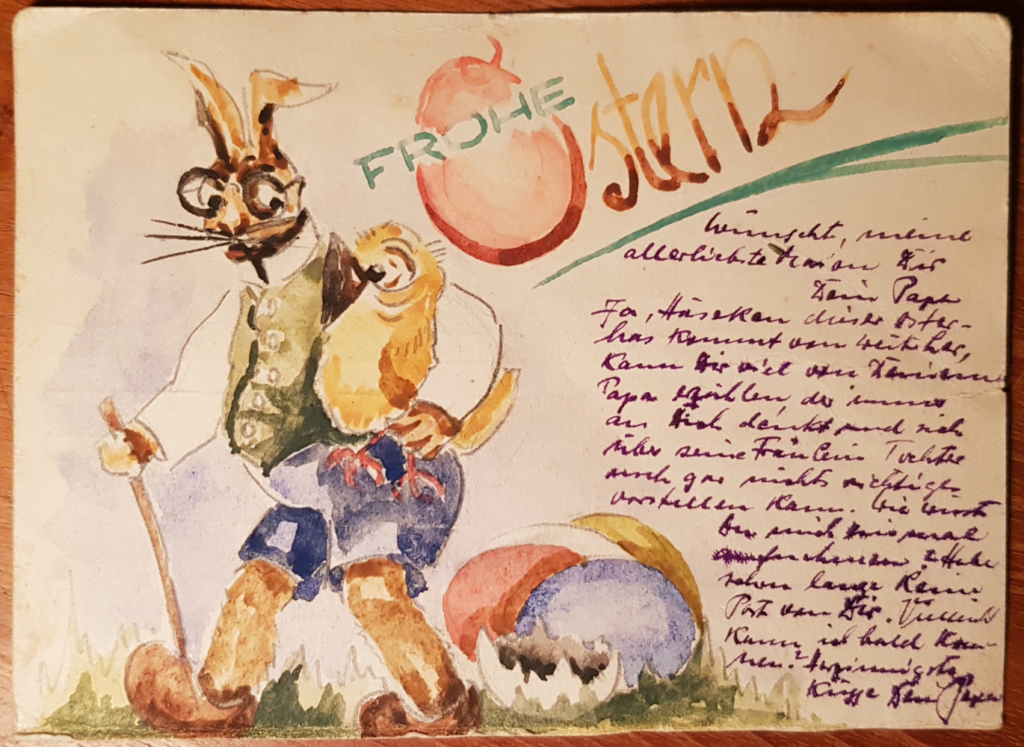

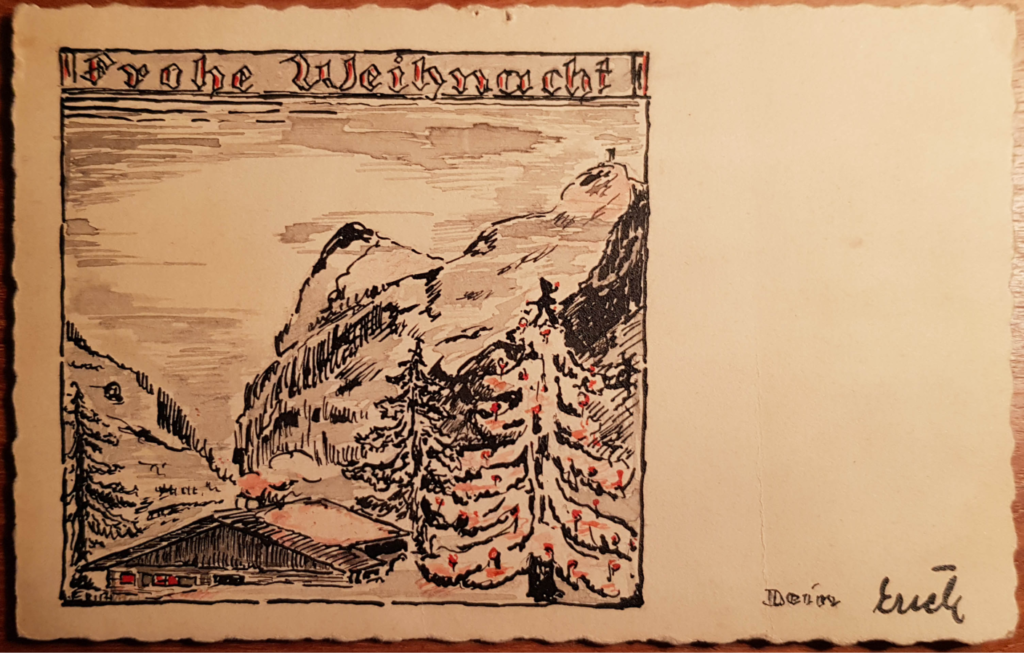

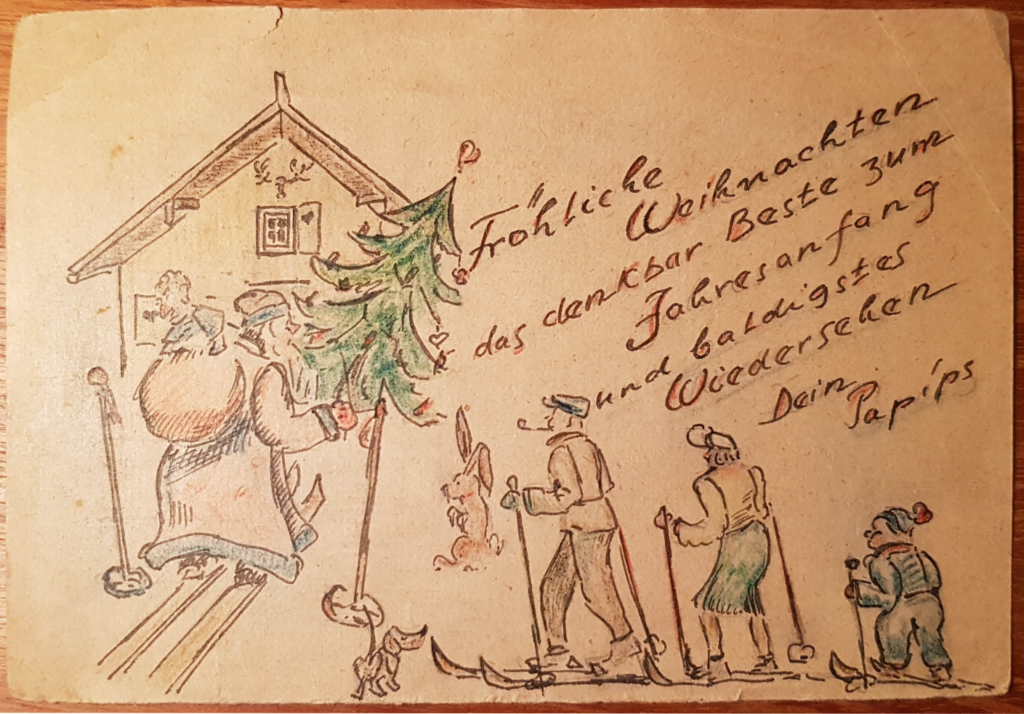

In my first years I received postcards from my father with some self-made drawings on them. He asked about me, my mother and asked for pictures of us, which kept him alive in the camp. One of his few belongings during the war was a little box with 6 watercolours, and sometimes he found the time to draw landscapes or little Russian dachas.

Later my father was said to be missing for three years and all letters my mother kept writing again and again came back with the note “zurück“. In many similar cases, women divorced their husbands or declared them dead in order to start again with a new partner. After years and years away from home, the men managed to return, after all, and found their wives remarried with new children.

During these years my American grandmother‘s family in the U.S. kept us alive by sending continuously parcels, thus supplying us with the basic foodstuff like sugar, coffee, condensed milk, salted butter, dried eggs, chocolate powder, white (!) flower, tobacco (“Prince Albert“), and cigarettes. With a packet of Camels or Lucky Strike you could get almost everything.

In April 1945 the U. S. occupying forces took charge in Munich. In the south of Munich, where we lived in the countryside, a lot of rich people had settled down in beautiful houses and villas. The Americans had a habit of throwing the owners out within 24 hours and occupy their houses for years and years to live in. Fortunately, our small cottage did not interest them. They were delighted when they found out my Granny was American.

Although it was strictly forbidden to fraternize with Americans, they came when it was dark and were glad to speak English with Granny and my mother. She had taught me all the American nursery rhymes and songs and when I sang to them, they gave me Hershey bars and chewing gums, things I had never seen in my life before.

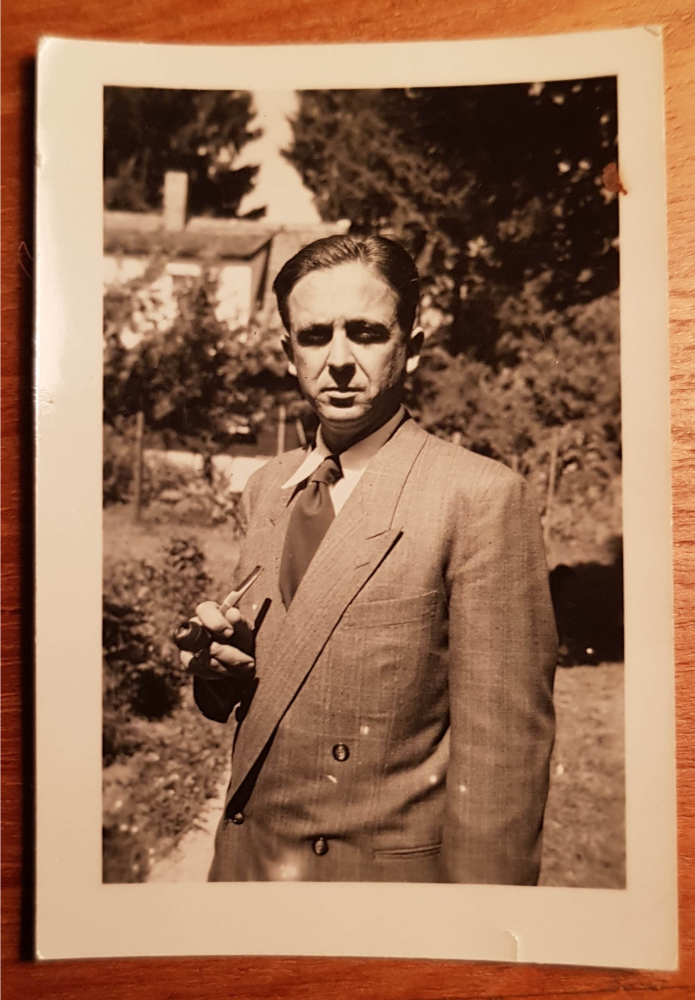

In 1947, after a long time with no word from my father, my mother got the news that he was still alive in a camp in far-away Siberia. He wrote he was hoping to be back in 1948. All was prepared for his home coming but it was not until summer 1949 that my mother could take him into her arms at Munich “Hauptbahnhof”.

I was anxiously waiting in the garden to see her walking down the road with the man I had known from pictures. He still wore his Russian outfit, a jacket and trousers, “valenki“, and a backpack.

Now I suddenly had a father too, sharing our life and my mother’s love. It was difficult for me to accept that. Now he was the one to say what to do and what not. I was not used to being teased and being laughed at. I was a very quiet child and used to friendly surroundings. I used to hide when he came home in the evening, because he always found fault with something I had done. I crept up to him waiting to have my ear pulled or sometimes get a slap when he thought it necessary.

Once he gave me a new 50 penny piece and laughed because I was so scared.

My parents built their own house on the same grounds. Later they had another daughter and the much-desired son, and I came in handy as a baby-sitter. But mostly the two of us were fighting until I left the house to get married.

Because of my father’s absence of 7 years from home, it was difficult to make this marriage work for both of my parents. Nowadays a divorce would be possible, but in this after-war society in Germany this would not have been endorsed for a high civil servant in a ministry, not to speak of the situation of a divorced woman. So, they stuck together like many others, and they got closer and closer only after my father had retired and my mother grew sick.

After my mother’s death, me and my siblings built up a new relationship to our father and he became a highly respected elderly in the family.

When he died, I was grieving for a good friend.